Notes from the Clean Architecture book

Here are some notes from the “Clean Architecture book”. I wrote notes only about things, which I hadn’t seen in popular articles before. Don’t consider this article as a short version of the book.

Notes

Components cohesion

Source: Chapter 14.

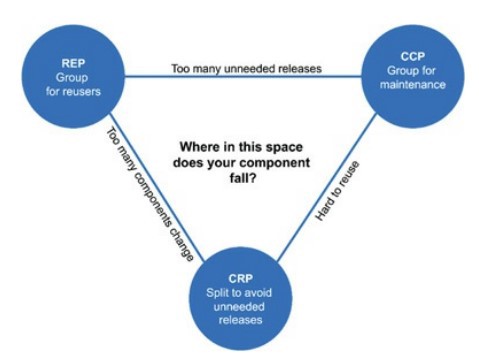

There is no single way to organize components, which fits every case. Values, which we’re hoping to get, are opposite to each other. There are 3 principles that guide components.

REP, the Reuse/Release Equivalence Principle: reusable components are tracked through the release process and have release numbers. Group related classes together to release in one update. Simplifies code reuse.

CCP, the Common Closure Principle: components should not have multiple reasons to change. Group classes that change at the same time for the same reason together.

CRP, the Common Reuse Principle(CRP): put classes that are reused together in the same components. Components should not contain classes that the client doesn’t use.

Example. Group classes according to actors who request changes, i.e. follow CCP. New features usually affect only one of the components. Simple maintenance. But you may have many unneeded releases. After dependency change, you need to recompile, retest, and redeploy dependable components even if changed classes weren’t used.

Cohesion principles tension diagram represents tradeoffs. The edges of the diagram describe the cost of abandoning the principle on the opposite vertex.

Acyclic Dependencies

Source: Chapter 14.

The “morning after syndrome”. Many developers work in parallel on the same code base. The Release is close. They push their changes to the same branch. The Project stops working.

The team can’t build a stable build. Now developers are focused on making their changes work with changes that someone else made. This is the morning after syndrome.

The ADP or the Acyclic Dependencies Principle is one of the possible solutions for the morning after syndrome.

Split the project into releasable components. Every component has an owner. A developer or a team is responsible for changes in components.

Let’s split a project into 3 components A(v1) -> B(v1) -> C(v1). Arrow means dependency, i.e. component A depends on B. v1 is a component’s version.

Now teams can independently work on their components. Team C published a new version v2, but teams A and B don’t use C(v2) until they need it. A(v2) -> B(v1) -> C(v1).

Team B integrates C(v2) when they are ready and publishes B(v2). Team A doesn’t have to integrate now. They can continue working on their features. A(v3) -> B(v1) -> C(v1)

When team A needs new capabilities of C and B they update. A(v4) -> B(v3) -> C(v2)

Granular update and integration remove the morning after syndrome.

Components can be updated independently only if your project doesn’t have cycle dependencies.

Add dependency from C to A. A(v1) -> B(v1) -> C(v1) -> A(v1) You can’t update components independently. Every update to A requires an update in C.

Humble object pattern

Source: Chapter 23.

I develop Android applications. Auto Testing there is challenging. Local JVM launches tests fast, but it can’t use classes from the Android framework, only pure java. I can launch auto tests on a device, but they’re so slow.

UI testing isn’t easy on any platform. Have you ever seen fast and reliable(not flaky) UI tests?

The Humble Object pattern helps with testing. Split the behaviors into 2 modules or classes. The first module is humble. It contains all hard-to-test behavior. For example, Android Views. The second module contains only testable behavior. For example, a presenter.

MVVM is a form of the Humble Object pattern. You can put all the UI logic to a View Model and cover it by unit tests. If views are dumb, as they should be, it’s okay to test them manually.

Single Responsibility Principle

Source: Chapter 7.

I thought that I understood SRP but I didn’t.

The Single Responsibility Principle has a misleading name. I thought it means that every class should do only one thing. But it’s not what SRP is about.

The Single Responsibility Principle states that: A module should have one, and only one, reason to change. This is not about a class having only one thing to do.

What’s a reason to change? Users and stakeholders are the “reasons to change” that the principle is talking about. Instead of the users and stakeholders, Uncle Bob uses the term “actors”.

The final version of SRP by Uncle Bob is: A module should be responsible to one, and only one, actor.

In other words, the SRP says to Separate the code that different actors depend on.

Business Rules

Source: Chapter 20.

Business rules are at the center of the Clean Architecture. The rest of the system is plugins.

A bank charges an N% interest for a loan. A clerk can calculate it using an abacus. This is an example of a Critical Business rule. Critical Business rules exist even if a system isn’t automated.

Critical Business rules work with some data. A loan requires the loan balance, interest rate, payment schedule. This data is called Critical Business data.

Critical Business rules + Critical business data = Entities of Clean Architecture. They exist even if a system isn’t automated. They represent the real world.

Some business rules define and constrain how an automated system works. They won’t be used in a manual environment.

Imagine a code that:

- Validates user input

- Gets and saves data using an abstract storage

- Invokes methods on entities That’s what Use Cases do in Clean Architecture.

Use Cases define how and when the Critical Business Rules within the Entities are invoked. Use Cases orchestrate Entities.

Entities shouldn’t know anything about the Use Cases. Entities are high level. They can be used in any application. They represent the real world. Use Cases are closer to I/O. They are specific for a single application.

End?

I would write mote notes if I had more time. I decided to abandon note writing at this stage.